PAULA: A Computational Substrate for Self-Organizing Biologically-Plausible AI

Introducing a novel formal neuron model that achieves 86.8% MNIST accuracy through purely local learning rules, homeostatic metaplasticity, and emergent cell assemblies, without backpropagation.

Abstract

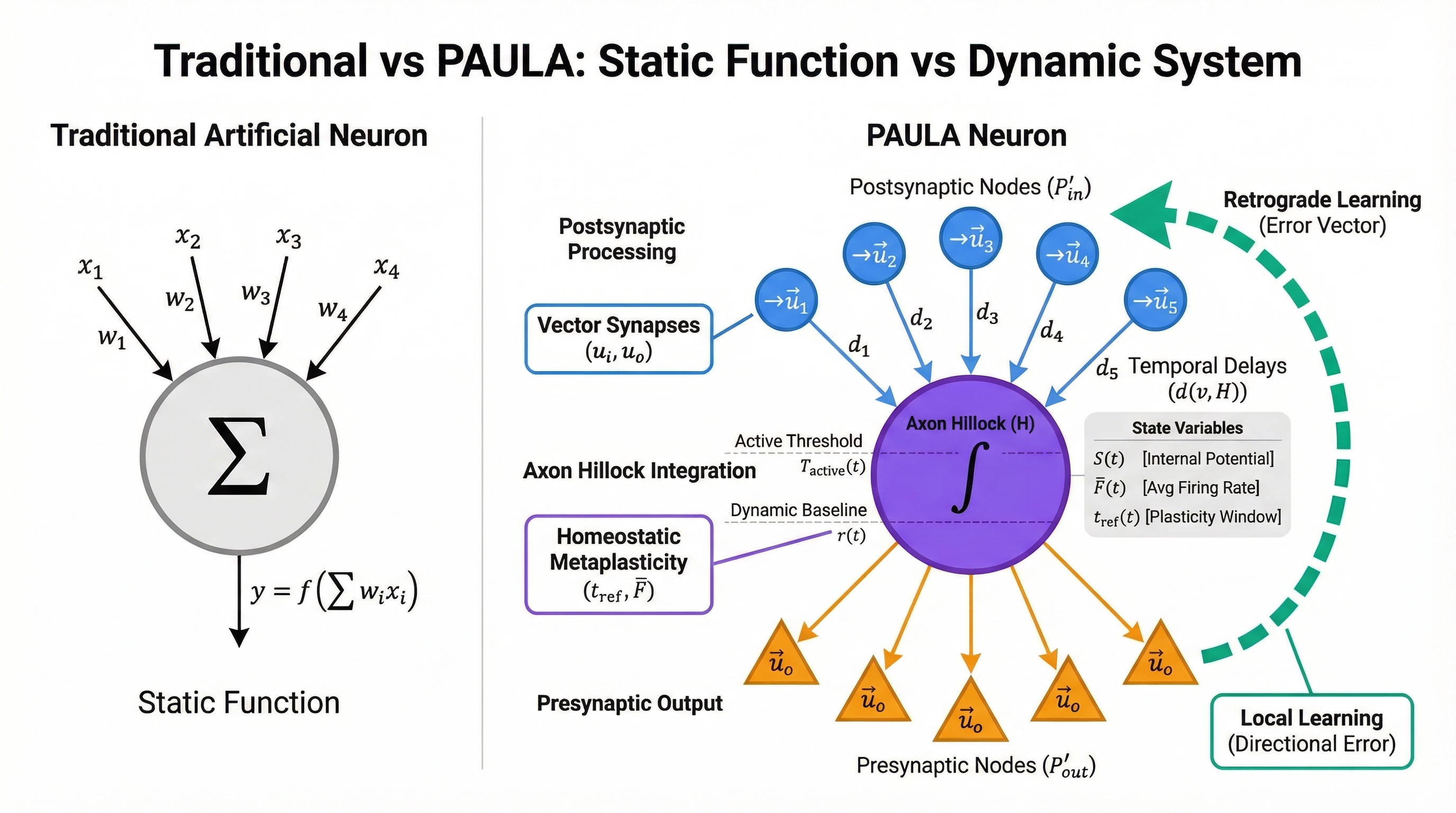

Modern Artificial Neural Networks (ANNs), despite their successes, diverge significantly from biological neural computation. They rely on static functions where learning occurs through global backpropagation rather than continuous local adaptation. We introduce PAULA (Predictive Adaptive Unsupervised Learning Agent), a biologically inspired neuron model incorporating: predictive coding for local error dynamics, retrograde modulation of vector-based synapses, and a homeostatic metaplasticity mechanism that adapts learning windows and thresholds to maintain bounded activity.

Using an in silico "Brain-EEG-fMRI" pipeline, we validate this model on MNIST. Results demonstrate extraordinary computational power even at the single-unit level (38.1% accuracy from one neuron) and reveal emergent network properties including graceful degradation under damage, superior performance with sparse architectures (86.8% accuracy), and spontaneous self-organization of functional cell assemblies. We conclude that PAULA represents a promising, validated substrate for developing more robust, adaptive, and scalable AI.

Key Findings

- Single neuron: 38.1% accuracy (4× baseline)

- Network: 86.8% MNIST accuracy without backpropagation

- Sparsity law: 25% connectivity outperforms 100% by 8+ points

- Stability requirement: Sparse networks converge; dense networks don't

- Emergent organization: Self-organizing cell assemblies without supervision

1. Introduction: Why a New Approach?

In traditional artificial neural networks, a neuron is a static mathematical function: it takes inputs, applies weights, sums them up, and passes the result through an activation function. A biological neuron, however, is something far more complex: a dynamic, adaptive agent that learns from purely local information and continuously adjusts to its environment (Moore et al., 2024; Liu et al., 2025; Patel et al., 2025).

This divergence suggests that current AI may be solving the wrong problem (Chen et al., 2025). Rather than approximating functions (input/output mappings), biological intelligence may be fundamentally about constructing and maintaining dynamical states that mirror environmental structure.

"Intelligence is not programmed; it emerges through continuous interaction with an environment. Any persistent system must model its environment to survive."

- Derived from Karl Friston's Free Energy Principle

Biological neural networks operate under fundamentally different principles:

- Local Learning: Neurons learn through local synaptic plasticity without global error signals

- Homeostatic Regulation: They maintain stability through self-regulation (Niemeyer et al., 2022; Shen et al., 2024)

- Metaplasticity: They adapt their learning rates based on activity history (Kuśmierz et al., 2017)

We developed PAULA to address this challenge by introducing a novel formal model for a network of dynamic, self-regulating computational units that learn continuously based on principles of local prediction (N'dri et al., 2025). This model synthesizes a wide range of neuroscientific discoveries into a single, coherent mathematical framework.

2. The PAULA Model

At its core, PAULA defines a "smart neuron": a biologically-inspired computational unit that goes beyond traditional artificial neural network primitives. In this section, we present a comprehensive specification of the model's architecture.

2.1 Graph Architecture

We formally define each neuron as a weighted, directed graph \(G = (V, E, d)\), where:

-

Node Sets: The node set \(V\) is the union of

three distinct processing sets:

- \(V_{P'_{in}}\): The set of all postsynaptic processing nodes

- \(V_{P'_{out}}\): The set of all presynaptic processing nodes

- \(\{H\}\): The axon hillock node

- Complete Node Set: \(V = V_{P'_{in}} \cup \{H\} \cup V_{P'_{out}}\)

- Edges: \(E \subseteq V \times V\) represents the directed connections between nodes

- Weights: A distance function \(d: E \to \mathbb{N}\) that assigns a travel time (in ticks) to each edge

2.2 Fundamental Units

-

Input Unit (\(i\)): A postsynaptic receptor. The

\(I_{adapt}\) set is a family of abstract functional subtypes:

- \(I_{adapt, Excitability}\)

- \(I_{adapt, Metaplasticity}\)

-

Output Unit (\(o\)): A presynaptic

neurotransmitter release. The \(O_{mod}\) set includes:

- \(O_{mod, Excitability}\)

- \(O_{mod, Metaplasticity}\)

2.3 Integrated Interaction Points (\(P′\))

Postsynaptic Point (\(P'_{in}\)): Its state is defined by a vector of receptor efficacies. Each synapse stores multiple "strengths" - one for information flow and additional ones for adapting to excitability and metaplasticity signals:

\[\vec{u_i} = (u_{info}, u_{adapt, Excitability}, u_{adapt, Metaplasticity}, ...)\]

Presynaptic Point (\(P'_{out}\)): Its output vector includes corresponding neuromodulator types. When a neuron fires, it releases signals that carry information and also modulate the receiving neurons' behavior:

\[\vec{u_o} = (u_{info}, u_{mod, Excitability}, u_{mod, Metaplasticity}, ...)\]

2.4 System State Variables and Parameters

Tick-Dependent Variables:

- \(S(t)\): Internal potential at the axon hillock \(H\)

- \(O(t)\): Output signal function from the hillock \(H\)

- \(t_{last\_fire}\): Timestamp of the last somatic firing event

- \(\bar{F}(t)\): The long-term average firing rate

- \(\vec{M}(t)\): The neuromodulatory state vector (\(\vec{M}(t) = (M_{Excitability}(t), M_{Metaplasticity}(t), ...)\))

- \(r(t), b(t)\): The dynamic primary and post-cooldown thresholds

- \(t_{ref}(t)\): The plastic causal time window for learning

Constant Parameters:

- \(\delta_{decay}\): Per-tick potential decay factor

- \(\beta_{avg}\): Decay factor for the average firing rate EMA

- \(\eta_{post}\): The postsynaptic learning rate

- \(\eta_{retro}\): The presynaptic learning rate for retrograde adaptation

- \(c\): The activation cooldown period in ticks

- \(\lambda\): The membrane time constant for the axon hillock

- \(p\): The constant magnitude of every output signal

- \(r_{base}, b_{base}\): Baseline values for the dynamic thresholds

- \(\vec{\gamma}\): Vector of decay factors for each component of \(\vec{M}(t)\)

- \(\vec{w}_r, \vec{w}_b, \vec{w}_{tref}\): Sensitivity vectors for dynamic parameters

2.5 State Transitions (The "Tick" and Graph-Based Dynamics)

The system evolves over discrete time steps \(dt\).

A. Neuromodulation and Dynamic Parameter Update:

-

Aggregate Neuromodulatory Input: For each

modulator type \(k\), calculate the total weighted input signal.

This sums up all the external "control signals" (like excitability

and metaplasticity) arriving at each synapse, weighted by how

sensitive that synapse is to each type:

\[\text{total\_adapt\_signal}_{k}(t) = \sum_{v \in V_{P'_{in}}} \left( O_{ext, mod, k}^{(v)}(t) \cdot u_{i, adapt, k}^{(v)}(t) \right)\]

-

Update Neuromodulatory State Vector: The neuron's

internal "state of mind" updates as an exponential moving average

- it slowly forgets past modulation while incorporating new

signals:

\[M_k(t+dt) = \gamma_k \cdot M_k(t) + (1-\gamma_k) \cdot \text{total\_adapt\_signal}_k(t)\]

-

Update Average Firing Rate: The neuron tracks how

often it fires over time. This running average is key for

homeostasis - it lets the neuron notice if it's too active or too

quiet:

\[\bar{F}(t+dt) = \beta_{avg} \cdot \bar{F}(t) + (1-\beta_{avg}) \cdot O(t)\]

-

Calculate Final Dynamic Parameters: These

equations set the neuron's firing thresholds based on its

neuromodulatory state. The thresholds \(r\) and \(b\) shift up or

down depending on the accumulated modulation:

\[\begin{align*} r(t+dt) &= r_{base} + \vec{w}_r \cdot \vec{M}(t+dt) \\ b(t+dt) &= b_{base} + \vec{w}_b \cdot \vec{M}(t+dt) \end{align*}\]

The plasticity window \(t_{ref}\) - which determines how long after firing a synapse can still strengthen - also adapts. If the neuron fires too often, the window shrinks; if too rarely, it expands:

\[\begin{align*} t_{ref\_homeostatic}(t) &= \text{upper\_bound} - (\text{upper\_bound} - \text{lower\_bound}) \cdot (\bar{F}(t) \cdot c) \\ t_{ref}(t+dt) &= t_{ref\_homeostatic}(t) + \vec{w}_{tref} \cdot \vec{M}(t+dt) \end{align*}\]

B. Input Processing & Propagation:

When a signal arrives at a synapse, it gets multiplied by that synapse's strength - this is how learning shapes perception:

-

When an external signal vector \(\vec{O}_{ext}\) arrives at a node

\(v \in V_{P'_{in}}\), the local voltage is computed as the signal

times the synaptic weight:

\[V_{local}(t) = O_{ext, info} \cdot u_{info}^{(v)}(t)\]

- This \(V_{local}\) potential is scheduled for arrival at the axon hillock \(H\) at \(t_{arrival} = t + d(v, H)\). The delay models realistic signal propagation time along the dendrite.

C. Signal Integration at Axon Hillock:

All incoming signals are summed at the cell body, but each is weakened by how far it had to travel (longer paths = more decay):

\[I(t) = \sum V_{local}(t) \cdot (\delta_{decay})^{d(v, H)}\]

D. Somatic Firing (Model H):

The core spiking dynamics. The membrane potential rises toward input and decays toward rest, like a leaky bucket:

-

State Evolution: The membrane potential \(S\)

evolves as a leaky integrator - it accumulates input while

constantly draining toward zero:

\[S(t+dt) = S(t) + \frac{dt}{\lambda} (-S(t) + I(t))\]

- Firing Condition: A spike occurs if \(S(t+dt) \ge T_{active}(t)\) and \(t+dt \ge t_{last\_fire} + c\). The neuron must exceed threshold AND wait out its refractory cooldown.

- Instantaneous Firing Dynamics: If a spike occurs at \(t_{fire}\), apply Model H reset rules (membrane resets, threshold jumps up to prevent immediate re-firing).

- Threshold Reset: If \(S(t)\) decays to near-zero, \(T_{active}(t)\) resets to \(r(t)\). This prepares the neuron for the next cycle of input.

E. Output and Learning:

- Presynaptic Release: A somatic spike propagates to all \(v \in V_{P'_{out}}\), causing release of \(\vec{u_o}^{(v)}\)

-

Dendritic Computation & Plasticity: At a synapse

\(v \in V_{P'_{in}}\) receiving \(\vec{O}_{ext}\):

-

Step 1: Directional Error Calculation - The

mismatch between what the synapse expected (its weight) and

what actually arrived. This local error drives learning:

\[\vec{E}_{dir}(t) = \vec{O}_{ext}(t) - \vec{u_i}^{(v)}(t)\]

-

Step 2: Temporal Correlation (Plasticity Gating)

- The key STDP-like mechanism. If the input arrived within the

plasticity window after the neuron fired, strengthen the

connection ("neurons that fire together, wire together"). If

too late, weaken it:

- Calculate \(\Delta t = t - t_{last\_fire}\) (time since last spike)

- If \(\Delta t \le t_{ref}(t)\), set direction = +1 (LTP - long-term potentiation)

- If \(\Delta t > t_{ref}(t)\), set direction = -1 (LTD - long-term depression)

-

Step 3: Postsynaptic Update - The actual

learning: adjust the synaptic weight proportionally to the

error magnitude, the current weight (multiplicative update),

and the temporal direction (LTP vs LTD):

\[\Delta u_{info}^{(v)}(t+dt) = \eta_{post} \cdot \text{direction} \cdot ||{E}_{dir}(t)|| \cdot u_{info}^{(v)}(t)\]

-

Step 4: Retrograde Signal and Presynaptic Update

- The postsynaptic neuron sends an error signal back to the

presynaptic neuron, allowing bilateral learning without global

supervision. The upstream neuron adjusts its output

accordingly:

\[\begin{align*} \vec{O}_{retro}(t) &= \vec{E}_{dir}(t) \\ \Delta \vec{u_o}(t+dt) &= \eta_{retro} \cdot \vec{O}_{retro}(t) \end{align*}\]

-

Step 1: Directional Error Calculation - The

mismatch between what the synapse expected (its weight) and

what actually arrived. This local error drives learning:

3. Experimental Methodology

Testing a new neuron model like PAULA required a carefully designed experimental setup. We could not simply train it like a regular neural network. We needed to create an entire research pipeline that treats the PAULA network as a living system we can observe, measure, and understand.

Our approach is analogous to studying a new organism in the wild: rather than placing it in a cage to see if it survives, we set up careful observations, controlled experiments, and multiple ways to measure its behavior.

3.1 Network Construction

We built deep perceptron-style networks made entirely of PAULA neurons. These are fully-connected layers where each neuron connects to every neuron in the next layer, but we systematically varied the connection density to see how sparsity affects learning and performance.

Each network was designed as a directed graph: neurons as nodes, synapses as edges with propagation delays. The interactive builder let us experiment with different layer sizes, depths, and connection patterns to find the sweet spot for biological plausibility and computational power.

Code: Network Builder

Interactive tool for designing PAULA networks with real-time visualization

code View Source3.2 Activity Recording

We fed MNIST images to the networks one by one, recording everything that happened inside the network during processing, not just the final answer.

For each image, we captured: membrane potentials (how excited each neuron was over time), plasticity windows (the dynamic learning sensitivity), neuromodulatory signals (internal control mechanisms), and spike timing (exact moments when neurons fired). This gave us a complete temporal fingerprint of how the network "thought" about each digit.

Code: Activity Recorder

Simulates network response to image sequences and logs all internal dynamics

code View Source3.3 Preparing Data for Analysis

Raw activity logs are messy, containing gigabytes of temporal data per network. We needed to extract meaningful features that a classifier could learn from. We focused on the key dynamical signatures: average membrane potentials over time, firing rates, and temporal patterns in the plasticity parameters.

This transformed the network's continuous internal dynamics into structured datasets that could be fed into standard machine learning pipelines for analysis and evaluation.

Code: Data Processor

Converts raw activity logs into PyTorch datasets with temporal feature extraction

code View Source3.4 Training the Pattern Decoder

To measure what the PAULA network actually learned, we trained an external spiking neural network classifier to decode the activity patterns. This serves as an "EEG" device that reads brain activity and translates it into recognizable categories.

The classifier used a simple but effective architecture: input layer for the extracted features, a couple of hidden layers with leaky integrate-and-fire neurons, and an output layer that predicts digit classes. We trained it using standard techniques: cross-entropy loss, Adam optimizer, and a learning rate of 0.0005. Crucially, the extracted features were not artificial constructs but genuine signatures of neural computation that happened inside PAULA units.

Code: Pattern Decoder

Trains SNN classifier to decode PAULA network activity patterns into digit predictions

code View Source3.5 Real-Time Evaluation

Final evaluation went beyond simple accuracy metrics. We ran the networks in real-time, watching how their "thinking" evolved over time. Some networks made quick decisions, others took longer to deliberate, revealing cognitive dynamics that static classifiers would miss.

The "thinking mode" experiments were particularly revealing: by giving networks extra processing time, we could see which digits required fast recognition versus deep deliberation, mirroring how humans process familiar versus complex stimuli.

Code: Live Evaluator

Real-time performance testing with temporal analysis and extended processing capabilities

code View Source3.6 Evaluation Protocol

To ensure comprehensive and reproducible results, we established a systematic evaluation protocol across all experiments. Every network architecture was evaluated under five distinct "thinking mode" configurations, where the network is given varying amounts of processing time (measured in simulation ticks) to integrate evidence:

- No thinking mode: Standard processing with base time allocation

- Thinking ×2: Extended processing time at 2× base duration

- Thinking ×3: Extended processing time at 3× base duration

- Thinking ×5: Extended processing time at 5× base duration

- Thinking ×7: Extended processing time at 7× base duration

This evaluation matrix was applied consistently across three distinct network architectures (single neuron, sparse networks, and dense networks), yielding 15 unique experimental conditions. All results reported in this paper are drawn from this comprehensive evaluation set, ensuring that observed phenomena are robust across different temporal integration scales and architectural configurations.

3.7 Structural Analysis

The real breakthrough came from analyzing what emerged inside the networks during learning. We used clustering algorithms to find functional groups of neurons that specialized in different aspects of the task, dynamical systems analysis to map the network's behavioral landscape, and performance analysis to understand scaling relationships.

This multi-modal approach revealed that PAULA networks do not just classify. They self-organize into sophisticated computational architectures that mirror biological neural systems.

Analysis Tools

Scripts for analyzing emergent network properties and visualization

4. Key Results

4.1 Single Neuron Computational Power

Our first experiments aimed to establish the computational capacity of a single PAULA neuron. Traditional artificial neurons achieve near-chance performance when used individually (≈10% on 10-class tasks). In contrast, a single adaptive neuron with homeostatic metaplasticity achieves remarkable performance on MNIST. This supports findings that single neurons represent powerful computational units capable of solving complex tasks (Jones & Kording, 2020).

Analysis of the neuron's temporal dynamics reveals that it encodes digit identity through characteristic membrane potential trajectories rather than static response magnitudes. Different digits produce different temporal patterns in the integrated response, with the external classifier learning to decode these trajectories. This demonstrates that computational richness emerges from temporal dynamics and adaptive mechanisms, not merely from parameter counts, validating the hypothesis that neurons are dynamical systems rather than static functions.

Result 1: The "Impossible" Test

A network consisting of a single neuron was tasked with classifying all 10 MNIST digits. The final, optimized result achieved a Top-1 accuracy of 24.1% and a the random baselines (10% and 30%).

Result 2: Single-Neuron Cognition

Applying "thinking mode" (granting additional processing time) pushed the Top-1 accuracy to 38.1%. Analysis revealed a distinct cognitive profile: the neuron showed "fast" recognition for simple digits ('0', '1') and "deliberative" recognition for complex temporal patterns (improving '5' from 0% to 71% Top-3 accuracy with extra time).

Single Neuron Performance with Extended Processing Time

| Condition | Top-1 Accuracy | Top-3 Accuracy |

|---|---|---|

| No thinking | 24.1% | 53.6% |

| Thinking ×2 | 31.3% | 51.8% |

| Thinking ×3 | 35.6% | 55.5% |

| Thinking ×5 | 37.5% | 53.5% |

| Thinking ×7 | 38.1% | 53.5% |

Beyond classification accuracy, the single neuron demonstrates remarkable dimensionality reduction: compressing 784-dimensional input into a 2-dimensional dynamical state (⟨S⟩, ⟨t_ref⟩) while preserving ~40% of class-discriminative information.

4.2 Systemic Properties & Architectural Principles

Next, we tested the behavior of multi-neuron networks, uncovering key design principles that emerge from PAULA's local learning dynamics.

Result 3: Graceful Degradation

When trained and tested on a dataset corrupted with a "state bleed" bug (temporal noise due to not reinitializing the network between different samples of the same digit label), the system's performance did not collapse. It maintained ~45% accuracy, demonstrating inherent robustness and resilience, a hallmark of biological systems.

Result 4: The Sparsity Scaling Law

A controlled experiment on networks with 144 neurons revealed a clear inverse correlation between connectivity and baseline performance:

- 100% Density: 64.2% Top-1 Accuracy

- 50% Density: 70.6% Top-1 Accuracy

- 25% Density: 76.1% Top-1 Accuracy

Result 5: The Architectural "Sweet Spot"

The best-performing model across all experiments was a smaller, 80-neuron sparse network, which achieved a Top-1 accuracy of 81.3%. Notably, bigger is not better: performance is a function of intelligent architecture (layer structure, neuron count, sparsity) rather than sheer scale, another key biological principle.

Detailed Performance Metrics

| Sparsity | Best Top-1 | Best Top-3 | Best Time | Avg Ticks to Correct | Prediction Stability |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 25% | 86.80% | 94.20% | 79 | 31.02 | 96.88% |

| 50% | 81.80% | 94.30% | 95 | 29.22 | 95.01% |

| 100% | 78.60% | 92.40% | 140 | 36.18 | 92.47% |

Network sparsity critically influences homeostatic dynamics and performance. The 25% sparse network achieves 86.8% accuracy, outperforming both 50% sparse (80.9%) and 100% dense (78.6%) configurations. Analysis of homeostatic parameters reveals the mechanism: dense networks show Layer 1 saturation, with neurons clustered at the \(t_{ref}\) lower bound (88-90 ticks), while sparse networks maintain \(t_{ref}\) diversity (88-96 ticks). This pattern indicates that full connectivity creates excessive input drive, pushing all neurons toward maximal selectivity and preventing the heterogeneity necessary for specialization. Sparse connectivity, by contrast, allows neurons to operate across the full homeostatic range, enabling differentiated responses and emergent cell assemblies.

4.3 "Thinking Mode" and Temporal Integration

To further characterize the network's cognitive dynamics, we applied extended processing time, what we call "thinking mode", to the best-performing sparse network:

⏱️ Temporal Evidence Integration

- Final Performance: 86.8% Top-1, 93.9% Top-3 accuracy

- Thinking Bonus: +15.2% absolute improvement

- Hypothesis Formation: Correct answer appears in Top-3 at ~16.8 ticks

- Deliberation & Confirmation: Final correct Top-1 decision at ~24.9 ticks

The model is not a static classifier. It is a dynamic decision-making engine that demonstrably integrates evidence over time, mirroring cognitive models like the Drift-Diffusion Model.

4.4 Emergent Cell Assemblies

Our clustering analysis, analogous to fMRI in neuroscience, revealed that PAULA networks spontaneously self-organize into 4-6 distinct functional "cell assemblies". These are groups of neurons that encode similar features:

Interactive Neuron Cluster Visualizations (hover for details, click+drag to zoom)

This emergent organization mirrors biological cortical columns, where neurons spanning multiple layers form functional units based on shared response properties. Critically, PAULA produces this organization without explicit architectural constraints or supervised grouping. It arises purely from homeostatic regulation interacting with task statistics.

The performance of the "EEG", referring to accuracy metrics, was shown to be a direct, predictable consequence of the "fMRI", the underlying cell assembly structure. For example, the model's difficulty with digit '7' was directly explained by the fact that no specialized cell assembly for it had emerged.

4.5 Attractor Landscapes

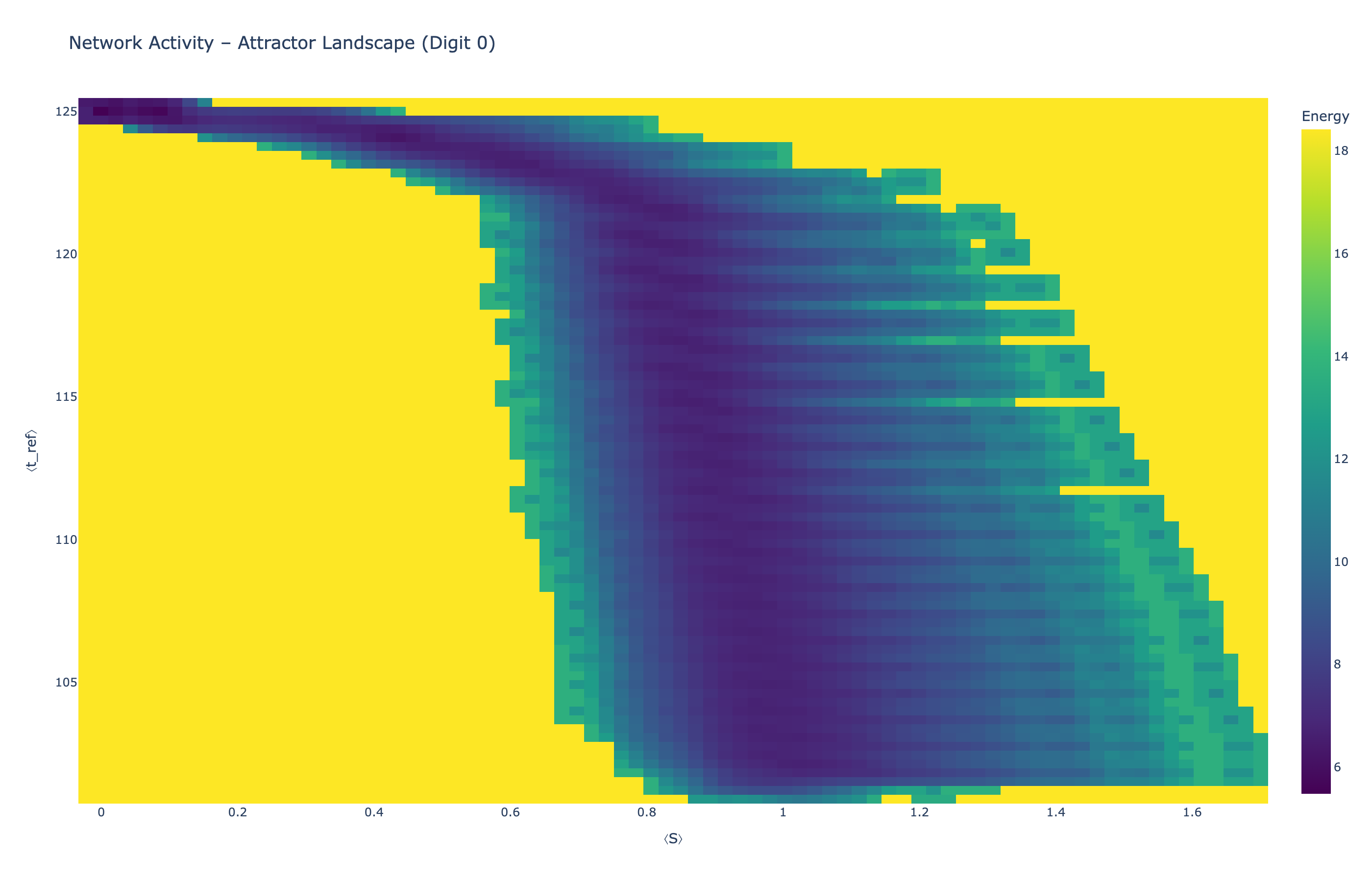

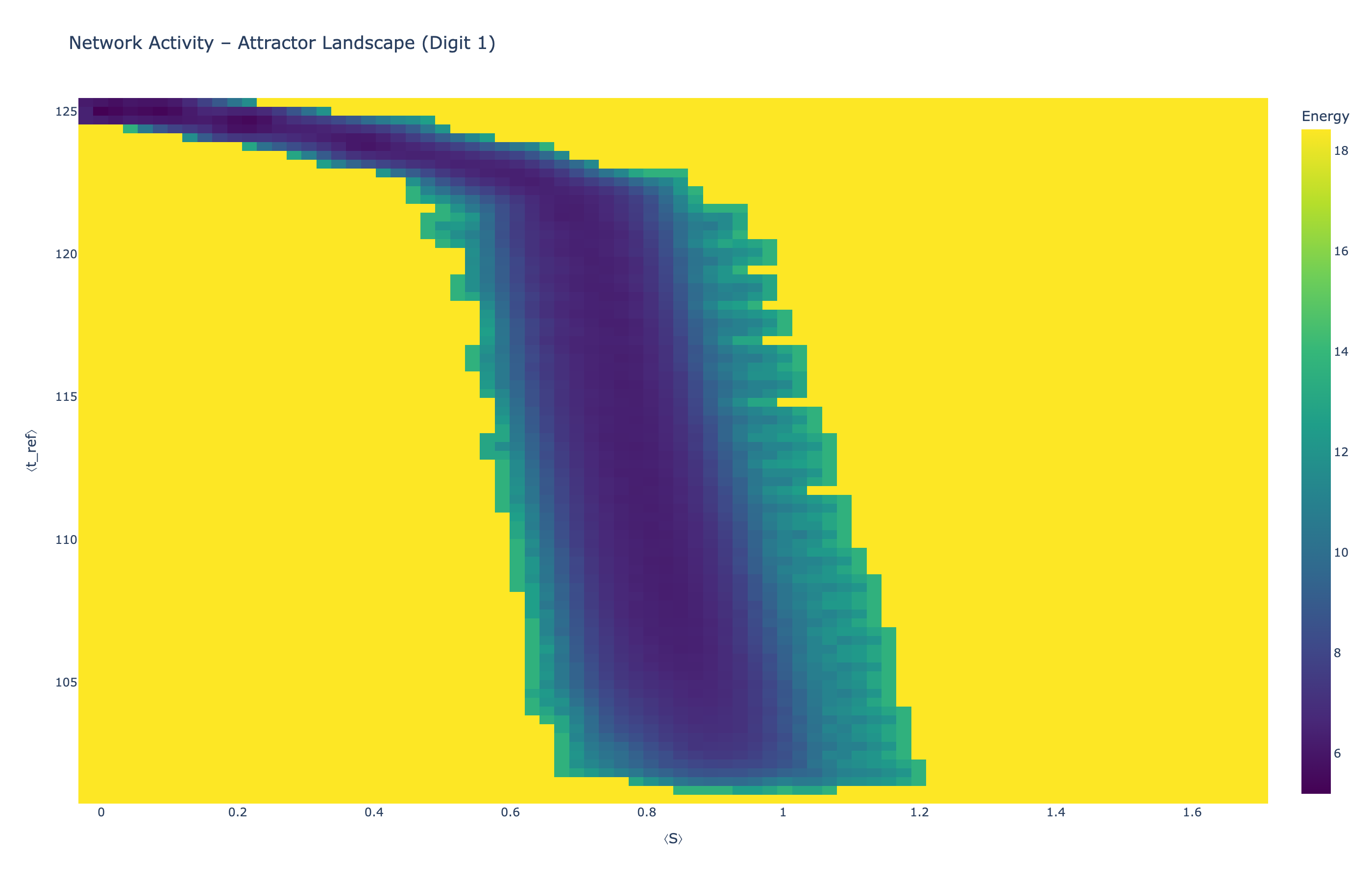

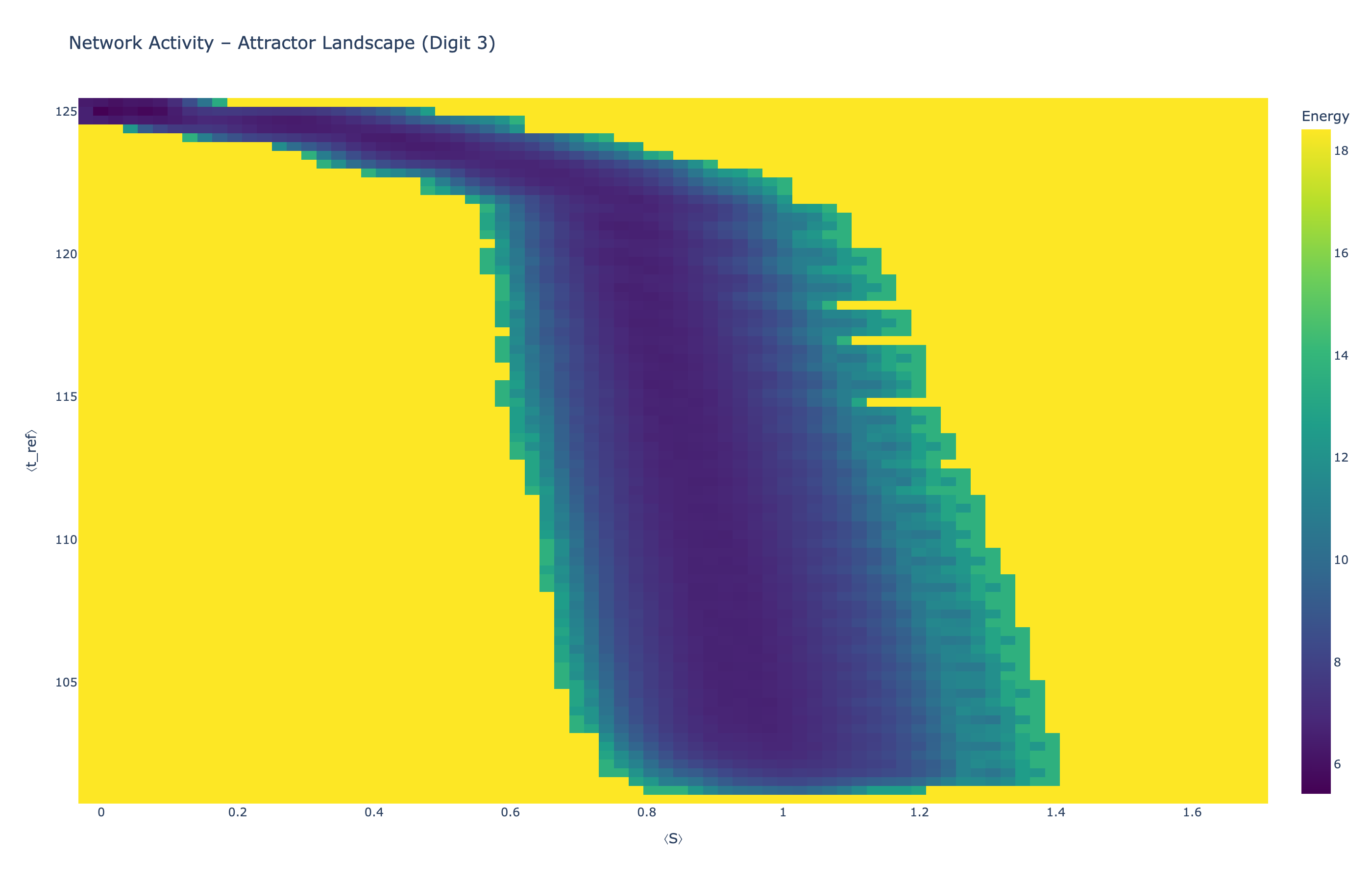

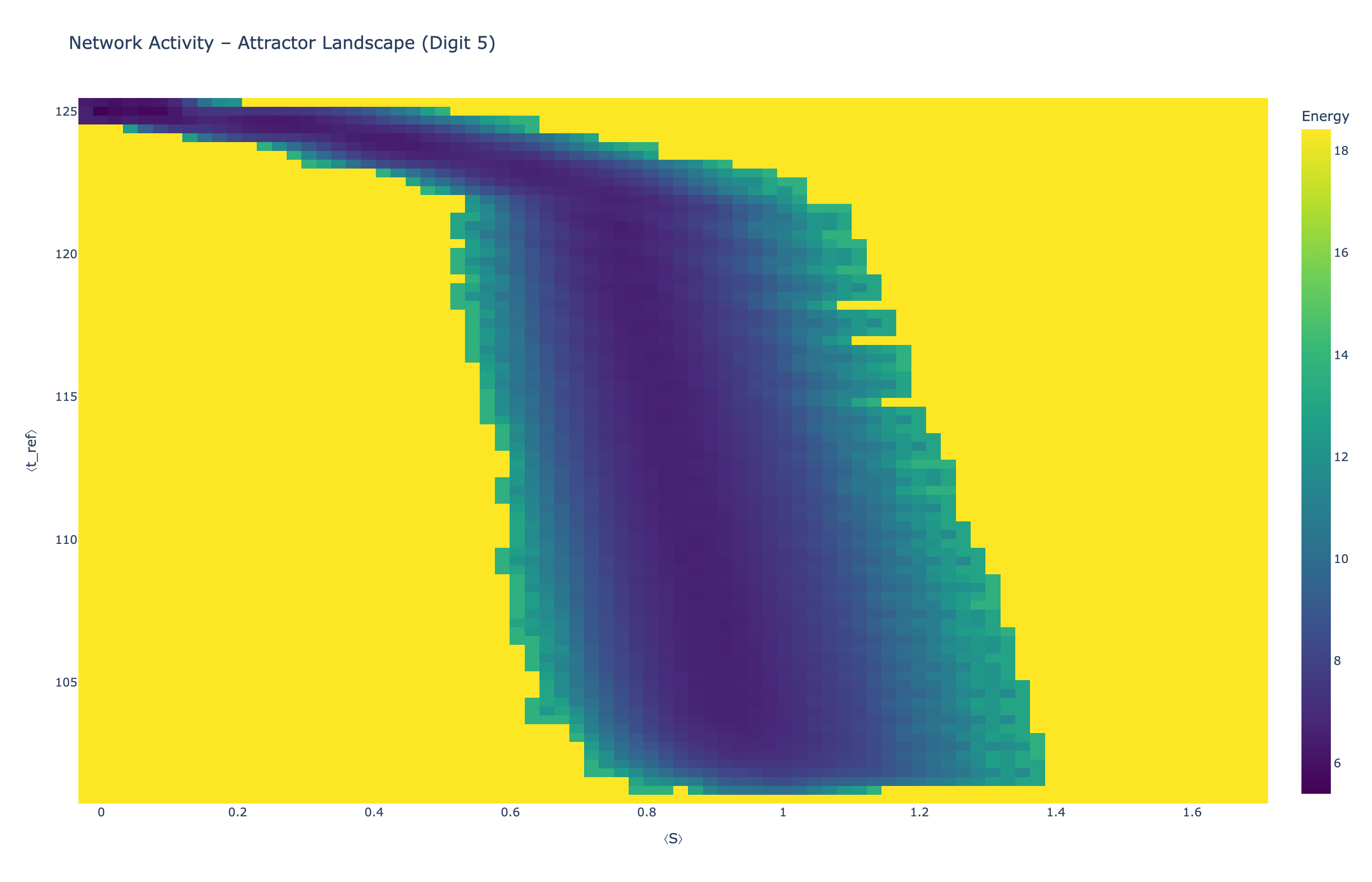

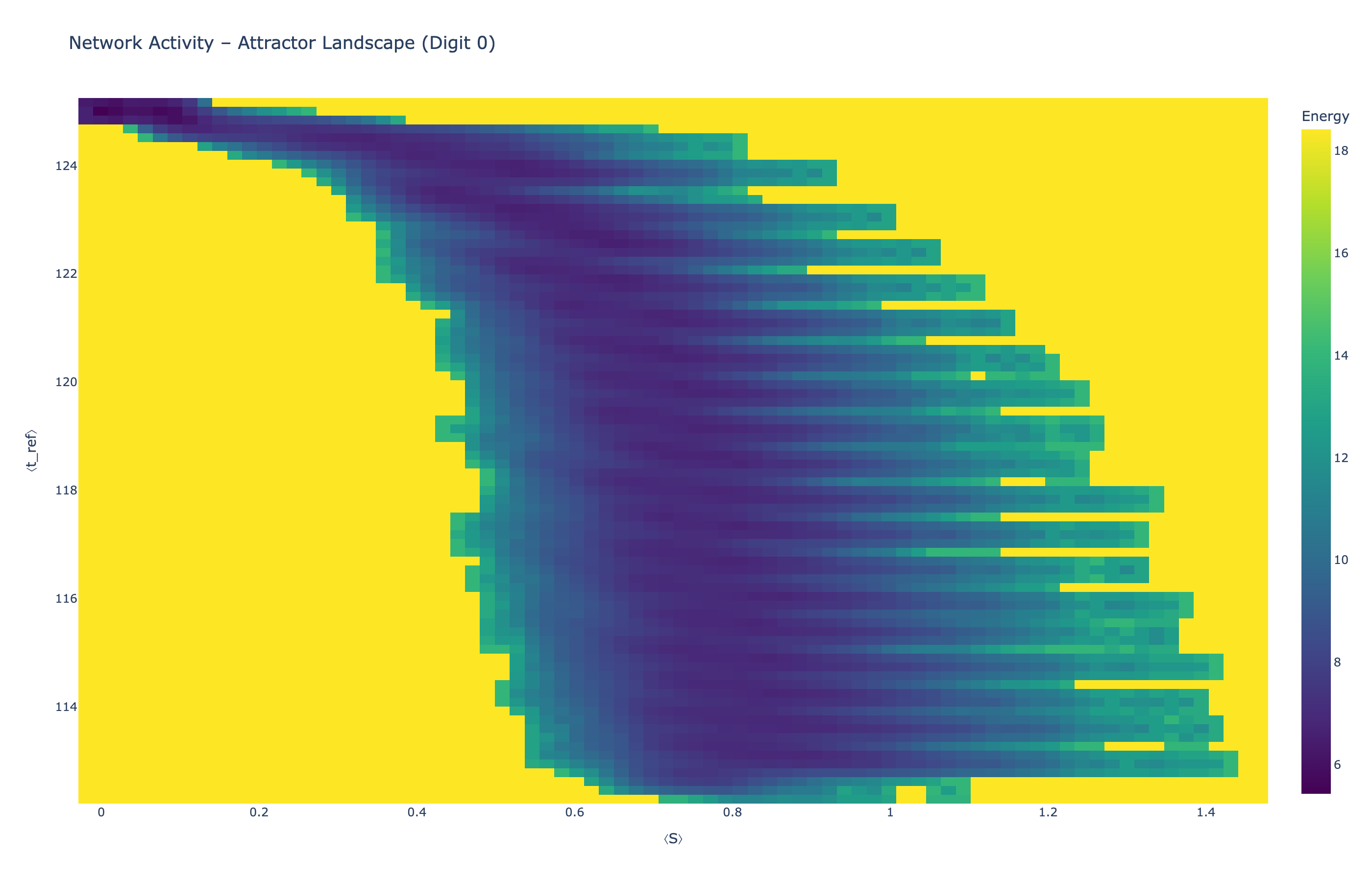

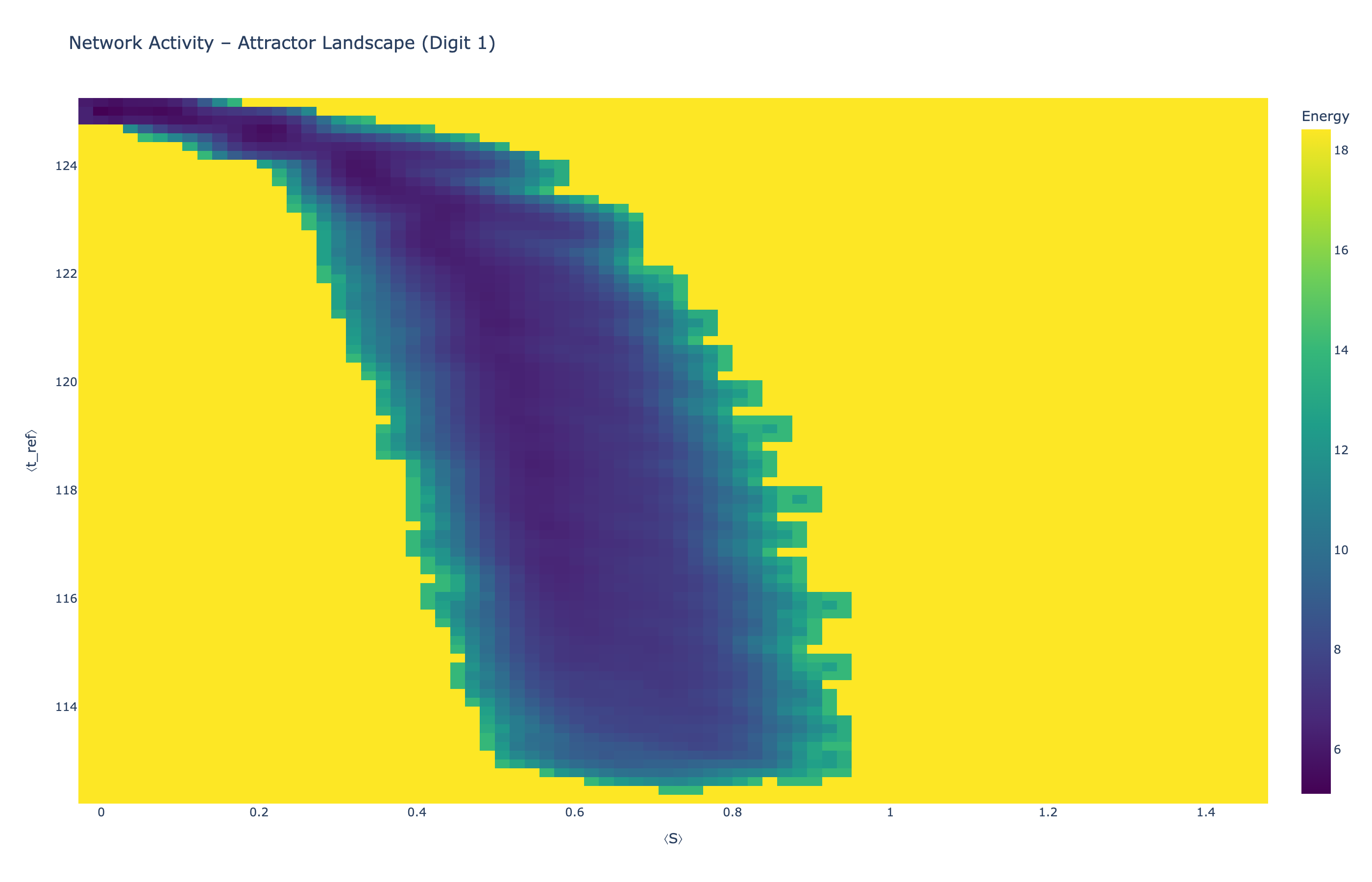

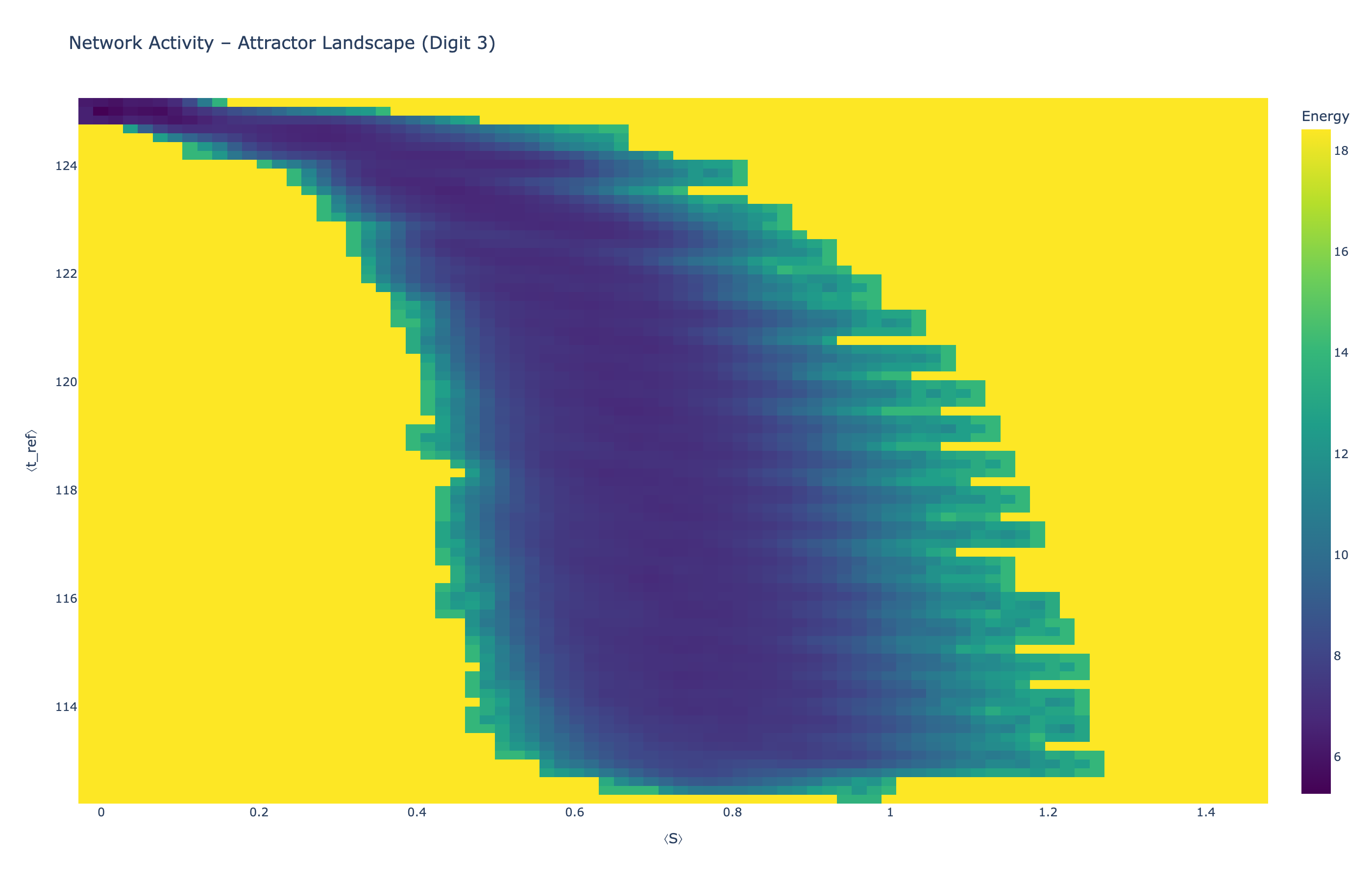

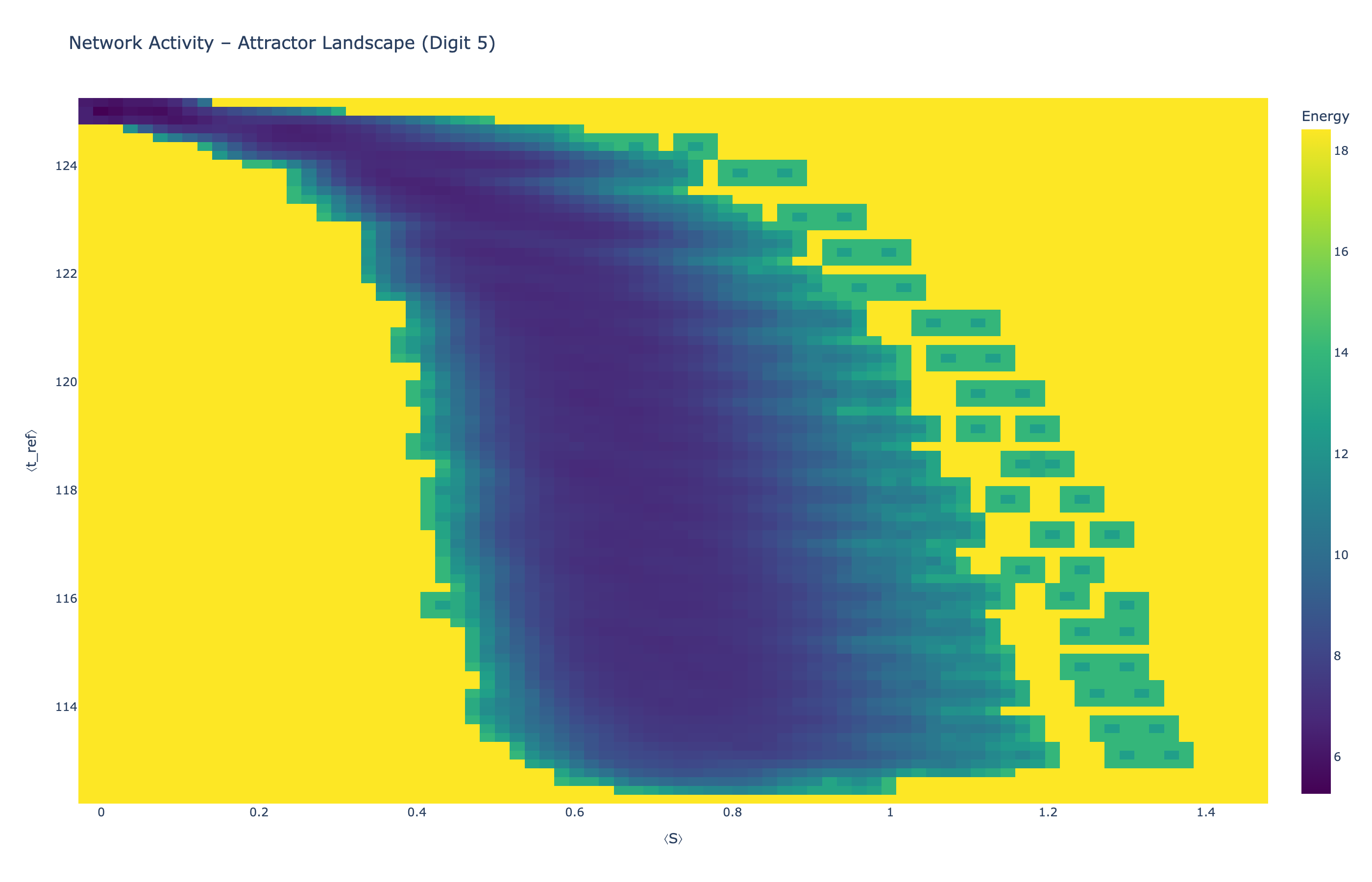

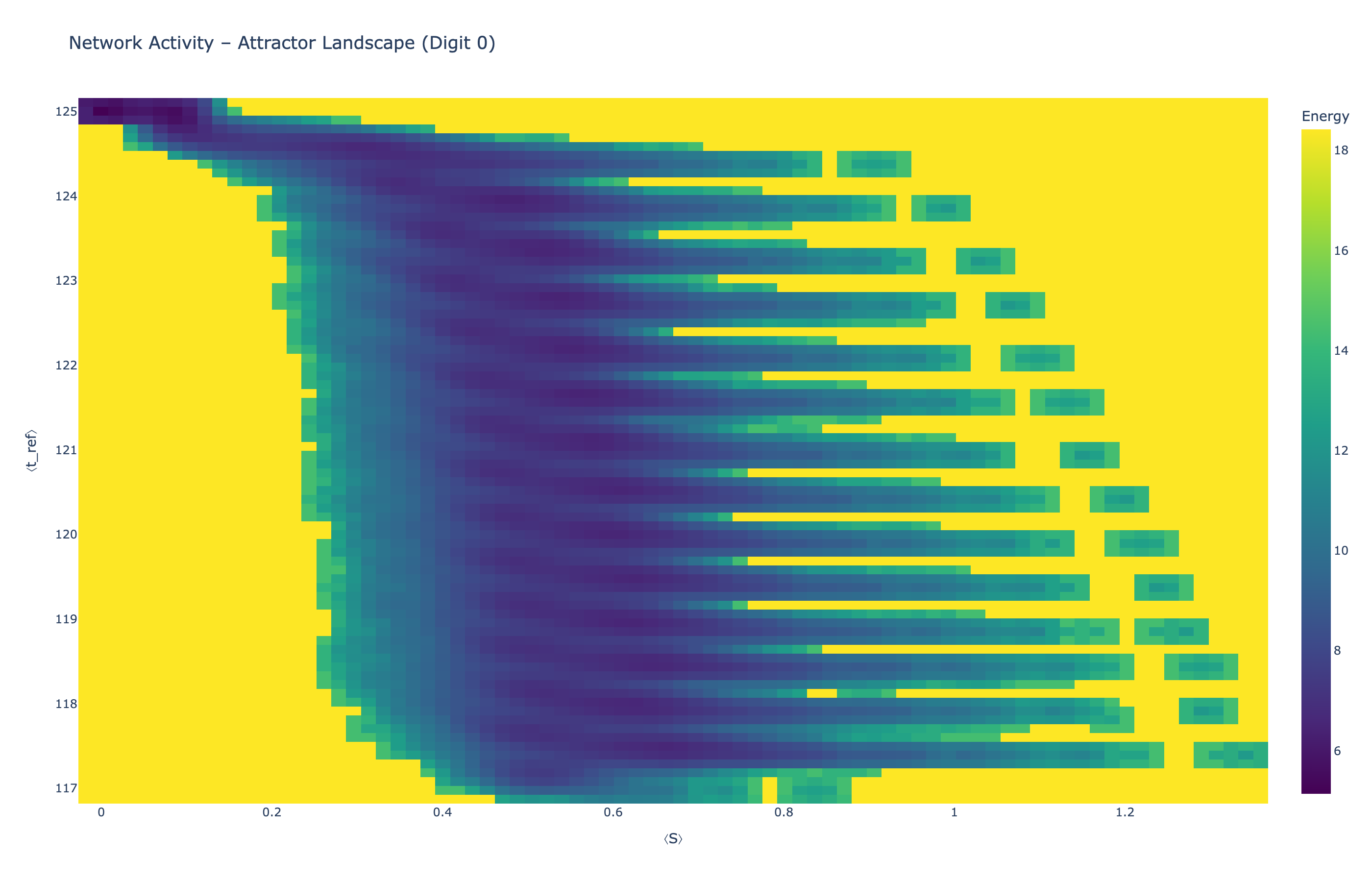

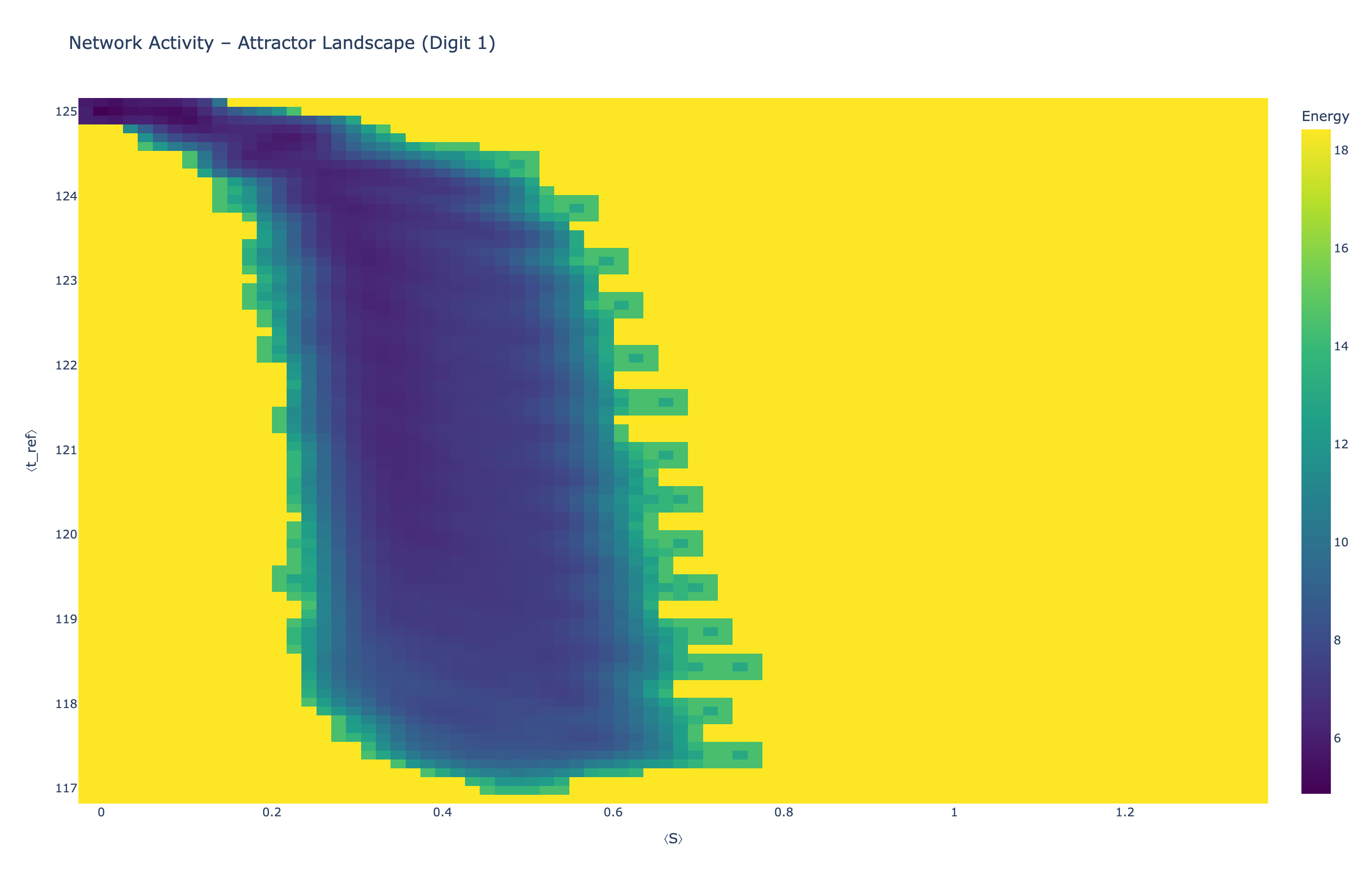

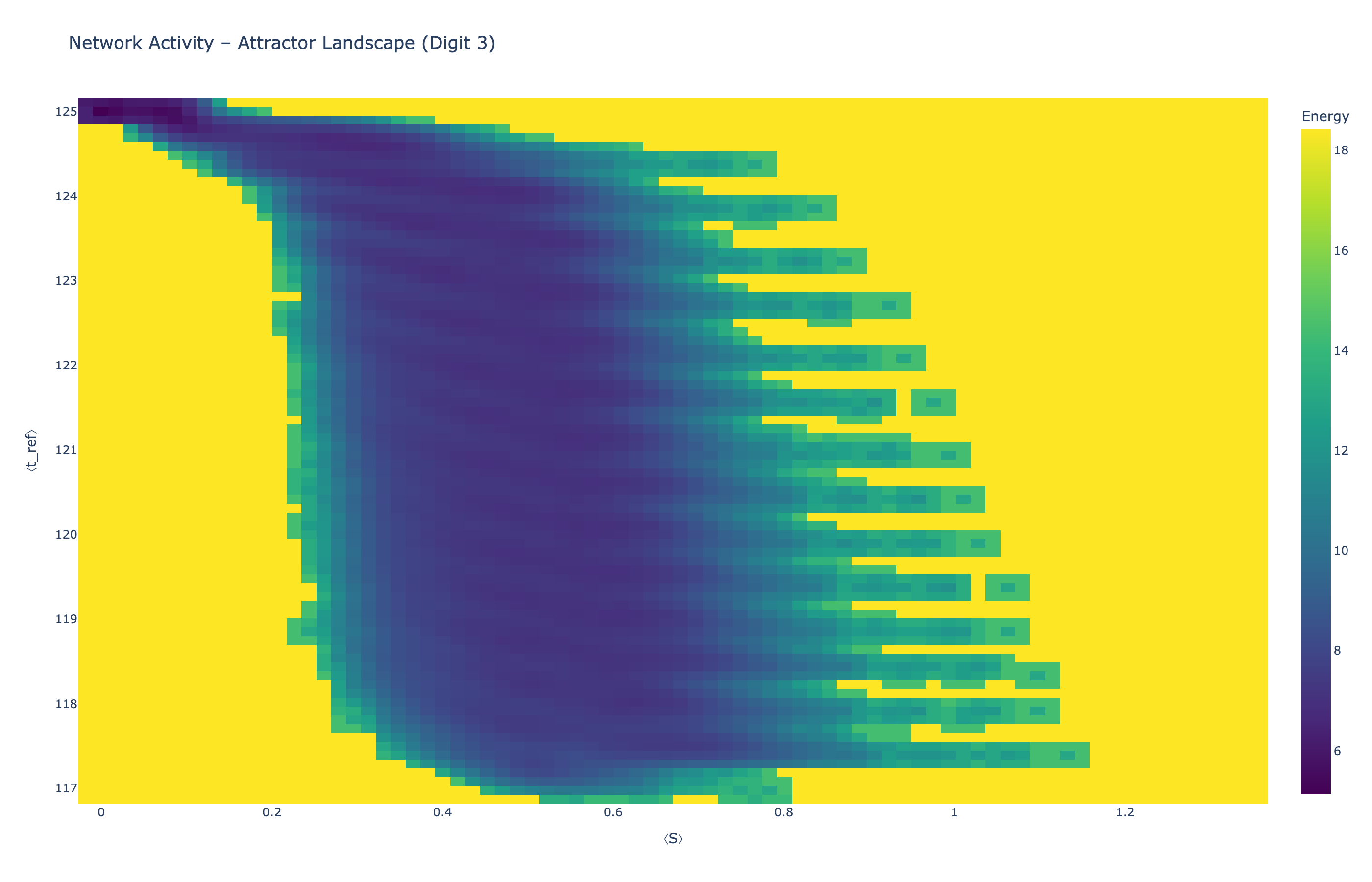

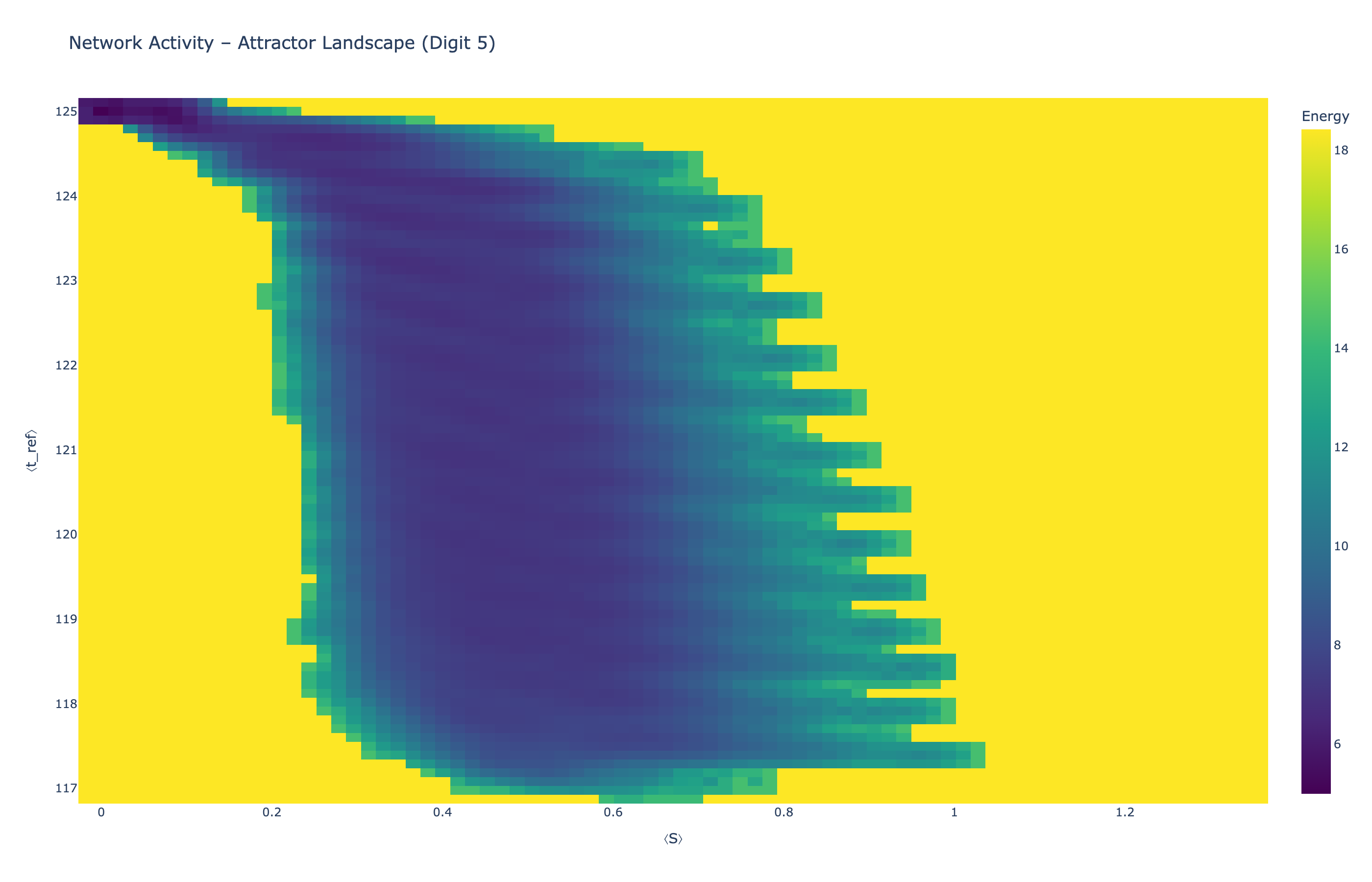

We analyzed network state dynamics in (⟨S⟩, ⟨t_ref⟩) space, revealing digit-specific topographies. The table below shows the full comparison across sparsity levels:

| Sparsity | Digit 0 | Digit 1 | Digit 3 | Digit 5 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dense (100%) |

|

|

|

|

| Sparse (50%) |

|

|

|

|

| Sparse (25%) |

|

|

|

|

Figure 5: Click any image to enlarge. Attractor landscapes in (⟨S⟩, ⟨t_ref⟩) state space for different digit classes across sparsity levels.

Interactive Attractor Landscapes (25% Sparse Network)

Each panel shows the energy landscape (KDE-smoothed density) for a different digit class. Dark blue regions indicate the network's preferred states (low energy basins); yellow regions represent rarely-visited configurations. Digit 1 exhibits a compact, centered attractor, while Digit 0 shows extended horizontal structure with multiple striations.

These distinct landscape geometries support the processual representation hypothesis: digits are encoded as characteristic dynamical regimes rather than static weight patterns. The network does not store 'digit 0' as a weight pattern but rather as the capacity to enter a specific oscillatory state.

5. Long-Term Dynamics and Scaling Principles

Our extended simulations (4,000–15,000 ticks) revealed fundamental scaling relationships between input dimensionality, network sparsity, and stabilization timescales.

Homeostatic Stabilization Scales With Input Dimensionality

MNIST networks (784 input dimensions) reached stable \(t_{ref}\) equilibrium at approximately 4,000 ticks, while CIFAR-10 networks (1,024 dimensions) required approximately 6,000 ticks. This suggests a general scaling principle:

📐 Scaling Law

Stabilization time ≈ 5-6× input dimensionality. For MNIST (28×28 pixels), convergence at 4,000 ticks (5.1× dim); for CIFAR-10 (32×32 pixels), at 6,000 ticks (5.9× dim). This enables prediction of convergence requirements for different input regimes.

Sparsity Is Necessary For Long-Term Stability

A critical finding: sparse networks achieve stable equilibrium while dense networks exhibit persistent instability, even after 15,000 ticks (4× the sparse network stabilization time).

⚠️ Key Insight

This transforms interpretation of our sparsity scaling law: sparse connectivity is not merely a performance optimization but a fundamental requirement for dynamical stability. Dense networks lack the architectural constraints necessary for homeostatic mechanisms to converge.

This directly parallels biological cortical development. Early postnatal cortex exhibits excessive synaptic density, which undergoes activity-dependent pruning during critical periods. Our results suggest this developmental trajectory is not merely metabolic optimization but a necessary path to stable neural dynamics.

6. Discussion

6.1 Processual Representation Through Dynamical Regimes

The finding that different digits drive the network into different dynamical regimes supports a processual view of representation. The network does not store 'digit 0' as a weight pattern but rather as the capacity to enter an oscillatory state characterized by 15-tick periodicity and growing variance amplitude. Classification is not retrieval but re-enactment: the network recreates the dynamics it previously associated with that input. This aligns with enactivist cognitive science and predictive coding frameworks, while providing computational instantiation with measurable state variables.

This processual view suggests rethinking how we design learning systems. Rather than asking 'what weights represent X?', we should ask 'what state corresponds to X?' and 'how does the system transition between states?'

- Memory becomes the landscape of attractors, not a database of patterns

- Learning becomes niche construction in state space, not gradient descent in weight space

- Forgetting becomes inability to access attractors, not weight overwriting, suggesting solutions to catastrophic forgetting through state-space partitioning

Extending this approach toward artificial general intelligence requires augmenting perceptual classification with goal-directed behavior and self-monitoring. Our broader research program proposes supervisory networks that observe the system's own state dynamics, creating meta-level representations. These supervisors could detect anomalies, specifically states that do not match expectations, regulate homeostatic setpoints based on task demands, and potentially give rise to self-awareness through recursive observation of observation. The current work establishes that state-based representations are computationally viable; future work must demonstrate they support flexible, goal-directed cognition.

6.2 Interpretability Challenges

An interesting paradox emerged from our analysis: functional specialization is evident through population analysis but resists traditional ablation studies. This actually validates the biological realism of the substrate. Like natural neural systems, our model exhibits graceful degradation (Result 3) and distributed representation, requiring neuroscience-appropriate analysis methods rather than standard ML interpretability techniques.

Unlike brittle engineered systems, PAULA networks exhibit biological-like damage tolerance, which precludes traditional ablation-based interpretability. Instead, we employ population-level analysis methods from neuroscience, demonstrating functional specialization through activity correlation rather than causal necessity. This property, often viewed as a limitation in artificial systems, is a defining characteristic of robust biological computation.

6.3 Global Context for Local Learning

While this work validates the core predictive learning and homeostatic metaplasticity mechanisms (Kuśmierz et al., 2017), the model's neuromodulation framework (\(\vec{M}(t)\) dynamics) enables future investigation of context-dependent learning, attention-like modulation, and task-switching, capabilities essential for embodied agents in dynamic environments.

Specifically, the model explicitly supports arbitrary neuromodulator types which can be seamlessly integrated in any internal process of a single neuron, from regulating the postsynaptic integration to affecting the decay factors of traveling signals and more.

6.4 Synaptic Weight Dynamics

Our validation demonstrates that the local learning mechanisms produce functional networks, but characterizing the emergent weight structures, learning trajectories, and the specific contribution of retrograde error correction requires dedicated analysis. Such investigation would reveal how the network's internal representations develop over training and could inform optimal initialization strategies.

Crucially, our model demonstrates that contrary to traditional AI systems, synaptic weights are not the only storage for information in neural networks. When the complex structure of a biological neuron is respected, it allows for a different type of information storage which does not rely solely on synaptic weight distribution or spike trains in SNNs. The dimensionality reduction power of a single computational unit (784 synapses reduced down to membrane potential and plasticity window with ~40% of preserved information) strongly supports that internal neuron dynamics and structure play a major role in bio-plausible computational systems (Ding et al., 2025; Intrator & Cooper, 1992).

The single neuron's capacity for intelligent dimensionality reduction suggests that biological neurons may function as nonlinear embedding units, projecting high-dimensional sensory input onto low-dimensional manifolds that preserve task-relevant structure. This spatiotemporal dimensionality reduction parallels recent work on nonlinear transforms for compression, which demonstrated that neural representations can achieve massive compression by transforming data into domains where redundancy is more efficiently encoded.

6.5 Sparsity Scaling Law and Network Architecture

The sparsity scaling law suggests a broader architectural principle: representation quality requires constraints on information flow. In dense networks, these constraints come from depth (vertical segregation); in shallow networks, they must come from sparsity (horizontal segregation). This explains both the success of deep learning architectures and the efficiency of biological sparse cortical networks, which employ both strategies simultaneously.

6.6 Architecture Search via Homeostatic Stability

Our long-term dynamics findings suggest a novel principle for neural architecture design: architectures should be optimized for homeostatic stability rather than immediate task performance. This criterion, selecting networks that achieve dynamical equilibrium within feasible timescales, provides a biologically-grounded alternative to gradient-based neural architecture search (NAS) approaches.

Traditional NAS methods optimize architectures through task-specific performance metrics, requiring extensive labeled data and computational resources for evaluating each candidate. In contrast, stability-based selection requires only observation of intrinsic dynamics under unlabeled input, as homeostatic convergence is a property of the network's response to input statistics, not task labels. An architecture that fails to stabilize, as we observed with dense networks, cannot form reliable internal representations regardless of task, filtering it out before expensive task evaluation.

The biological plausibility of this approach is evident in cortical development. Early cortex exhibits random, excessive connectivity, which undergoes activity-dependent refinement through synaptic pruning, homeostatic scaling, and inhibitory tuning. These mechanisms do not optimize for specific tasks (the infant does not yet know what tasks it will encounter) but rather establish stable, adaptive computational substrates that can subsequently learn diverse skills.

The discovered scaling law of stabilization time being approximately 5× input dimensionality provides quantitative guidance for architecture design:

- Small inputs (MNIST: 784D → 4,000 ticks): full homeostatic training is computationally feasible

- Moderate inputs (CIFAR-10: 1,024D → 6,000 ticks): extended training remains viable

- Large inputs (ImageNet: 224×224 = 50,176D → ~250,000 ticks predicted): monolithic architectures become impractical, suggesting the need for hierarchical processing where lower layers stabilize on local receptive fields before deeper layers integrate globally

6.7 Biological Parallels: Development, Pruning, and Stability

Our finding that sparse networks achieve stability while dense networks remain perpetually unstable provides computational support for a long-standing puzzle in neurodevelopment: why does cortex initially overproduce synapses, only to eliminate 40-60% during postnatal critical periods? Traditional explanations emphasize metabolic efficiency or Darwinian selection of "useful" connections. Our results suggest a complementary mechanism: pruning is necessary for dynamical stability.

In early postnatal cortex, synaptic density peaks at approximately twice the adult level, then undergoes activity-dependent pruning during critical periods. This developmental trajectory parallels our findings: dense initial connectivity (analogous to 100% networks) creates unstable dynamics where homeostatic mechanisms cannot converge. Pruning to sparse adult levels (analogous to 25% networks) enables stabilization. The brain may not "know" which specific connections to eliminate; instead, activity-dependent mechanisms remove connections until the network enters a stable dynamical regime where homeostatic regulation can converge.

This interpretation is consistent with experimental observations that synaptic pruning is triggered by neural activity patterns and regulated by homeostatic mechanisms. Networks with excessive connectivity show heightened excitability and instability. Pruning reduces this instability, enabling refinement of functional circuits. Disruptions to this process, as occur in neurodevelopmental disorders where pruning is impaired, result in networks with persistent instability, potentially underlying the sensory hypersensitivity and information processing deficits observed in autism spectrum disorders and schizophrenia.

The cross-layer functional organization that emerges in our stabilized sparse networks further parallels cortical development. Orientation columns in V1, for instance, develop through spontaneous activity-driven self-organization before visual experience, with neurons across layers coordinating based on response properties rather than anatomical proximity. Our model reproduces this emergent organization through purely local homeostatic mechanisms, supporting theories that cortical columns arise from stabilization of initially random connectivity under homeostatic constraints.

These parallels position PAULA not merely as a classification model but as a computational framework for investigating principles of neural development and plasticity. Future work can use the model to test hypotheses about developmental disorders (does impaired pruning prevent stabilization?), critical period timing (when does functional organization emerge?), and the interplay of activity-dependent and homeostatic plasticity in sculpting stable, adaptive neural circuits.

7. Limitations

Extension to Natural Images

Preliminary experiments on CIFAR-10 natural images provide evidence for the generality of PAULA's homeostatic principles while highlighting architectural requirements for different input regimes. CIFAR-10's higher dimensionality (1,024D vs MNIST's 784D) requires proportionally longer stabilization according to the discovered scaling law: extended simulations confirmed networks reached homeostatic equilibrium at approximately 6,000 ticks, consistent with the predicted 5-6× dimensionality relationship.

However, initial experiments using MNIST-optimized training durations (300-1,000 ticks) were insufficient for convergence, resulting in unstable dynamics and near-chance performance (~15% accuracy). This highlights the importance of training duration as an architectural hyperparameter that must scale with input dimensionality. The scaling law provides principled guidance for setting training duration based on input size rather than empirical search.

Additionally, CIFAR-10's lower pixel-level variance (eta-squared: 6.8% vs MNIST's 34%) and complex spatial structure revealed architectural constraints of the current implementation. Networks used flattened pixel inputs without spatial preprocessing, forcing the model to learn spatial relationships from scratch through purely temporal dynamics. While homeostatic stabilization occurred as predicted, the multiplicative synaptic rule (\(V_{local} = O_{ext} \cdot u_{info}\)) functions as a variance amplifier: high-variance inputs (MNIST) provide strong signal for temporal dynamics to amplify, while low-variance inputs (CIFAR-10) offer insufficient substrate despite achieving stable internal dynamics.

Extension to natural images would benefit from:

- Spatial preprocessing (convolutional feature extraction) before temporal processing

- Hierarchical architectures that process local regions before global integration

- Architectural adaptations that enhance temporal discrimination of low-variance inputs

Our work suggests the need for preprocessing mechanisms that concentrate input variance, mimicking retinal and early cortical processing which enhances local contrast. Ultimately, PAULA's MNIST requires architectural adaptation, a property shared by all neural network approaches, biological and artificial alike.

8. Conclusion

This work makes three contributions:

- A formal model of homeostatic metaplasticity integrating dynamic learning windows with vector synapses and local predictive learning

- Empirical validation showing this mechanism enables competitive performance (86.8% MNIST) with purely local rules

- Discovery that different input classes drive networks into distinct dynamical regimes with characteristic temporal signatures

A network of these adaptive neurons is not merely a collection of individual units. It is a self-organizing system whose primary emergent function is the construction of a robust internal model. The model's Hebbian learning rule naturally gives rise to cell assemblies - interconnected groups of neurons that represent stable concepts, objects, and causal relationships in the environment. Information is therefore not stored in any single neuron but is encoded in the distributed patterns of activity across these populations.

A critical challenge in any plastic network is maintaining stability. This model addresses the problem from the bottom up through homeostatic plasticity. Each neuron's metaplasticity rule (Kuśmierz et al., 2017), which adjusts its learning window based on its average firing rate, provides a powerful local stabilizing force. If a circuit becomes over-excited, its constituent neurons automatically reduce their learning sensitivity, preventing runaway potentiation and ensuring the network's internal representations remain stable.

This model's architecture provides a framework for addressing several key open problems across multiple disciplines:

In AI and machine learning, it offers a plausible, local alternative to the credit assignment problem solved by backpropagation, using a retrograde signaling loop to provide targeted feedback. It addresses continual learning and catastrophic forgetting through its inherent homeostatic plasticity, and its sparse, event-driven nature as a Spiking Neural Network (SNN) makes it a candidate for highly energy-efficient computation.

In neuroscience, the model provides a unified mathematical framework for exploring how different forms of plasticity, Hebbian, homeostatic, and neuromodulatory, can coexist and interact. Its graph-based structure provides a testable platform for investigating the role of dendritic computation, and its use of sensitivity vectors offers a quantitative hypothesis for the function of neuromodulatory diversity.

In cognitive science and philosophy, the model provides a plausible mechanistic substrate for several theories. The temporal synchronization of its neurons can address the "binding problem" of perception. Its self-organizing nature aligns with theories of internal representation where the brain builds a predictive model of its environment. And its capacity for information integration, global coordination, and self-reflection aligns with key principles of scientific theories of consciousness, such as Integrated Information Theory (IIT) and Global Workspace Theory (GWT).

These results demonstrate that local learning with homeostatic regulation is viable for complex tasks and open paths toward neuromorphic implementations and continual learning systems, bridging the gap towards nonbiological life forms.

9. Related Work

This work builds upon and relates to several important research directions in neuroscience-inspired AI:

- The Universal Landscape of Human Reasoning (Chen et al., 2025)

- Advancing the Biological Plausibility and Efficacy of Hebbian Convolutional Neural Networks (Nimmo & Mondragón, 2025)

- Objective Function Formulation of the BCM Theory of Visual Cortical Plasticity (Intrator & Cooper, 1992)

- A Computational Perspective on NeuroAI and Synthetic Biological Intelligence (Patel et al., 2025)

- Neural Brain: A Neuroscience-inspired Framework for Embodied Agents (Liu et al., 2025)

- Continuous Thought Machines (Darlow et al., 2025)

- The Dragon Hatchling: The Missing Link between the Transformer and Models of the Brain (Kosowski et al., 2025)

- Implementing Spiking World Model with Multi-Compartment Neurons for Model-based Reinforcement Learning (Sun et al., 2025)

- An Accurate And Fast Learning Approach In The Biologically Spiking Neural Network (Nazari & Amiri, 2025)

- Training High-Performance Low-Latency Spiking Neural Networks by Differentiation on Spike Representation (Meng et al., 2023)

- Synaptic Plasticity Dynamics for Deep Continuous Local Learning (DECOLLE) (Kaiser et al., 2020)

- Keys to Accurate Feature Extraction Using Residual Spiking Neural Networks (Vicente-Sola et al., 2022)

- Learning with Three Factors: Modulating Hebbian Plasticity with Errors (Kuśmierz et al., 2017)

- Three-Factor Learning in Spiking Neural Networks: An Overview of Methods and Trends from a Machine Learning Perspective (Mazurek et al., 2025)

- Predictive Coding Approximates Backprop along Arbitrary Computation Graphs (Millidge et al., 2020)

- On the Adversarial Robustness of Spiking Neural Networks Trained by Local Learning (Lin & Sengupta, 2025)

- Graph World Model (Feng et al., 2025)

- Advancing Spatio-Temporal Processing in Spiking Neural Networks through Adaptation (Baronig et al., 2025)

- Information-computation trade-offs in non-linear transforms (Ding et al., 2025)

- Brain-inspired Artificial Intelligence: A Comprehensive Review (Ren & Xia, 2024)

- Learning the Plasticity: Plasticity-Driven Learning Framework in Spiking Neural Networks (Shen et al., 2024)

- The neuron as a direct data-driven controller (Moore et al., 2024)

- Hebbian Deep Learning Without Feedback (Journé et al., 2023)

- Biophysical models of intrinsic homeostasis: Firing rates and beyond (Niemeyer et al., 2022)

- Predictive Coding Light (N'dri et al., 2025)

- Can Single Neurons Solve MNIST? The Computational Power of Biological Dendritic Trees (Jones & Kording, 2020)

- STDP-based spiking deep convolutional neural networks for object recognition (Kheradpisheh et al., 2017)

🔗 Resources